There's a lot of interest in under-representation of women in certain science subjects, but in psychology, there's more concern about a lack of men. A quick look at figures from UCAS* (Universities & Colleges Admissions Service) shows massive differences in gender ratios for different subjects. In figure 1 I’ve plotted the percentage of women accepted for subjects that had at least 6000 successful applicants to degree courses in 2011.

|

| Fig. 1. % Females accepted on popular UK degree courses 2011 |

- Oxford University, where I work, may be biased in favour of men

- The proportions of women decline with career stage

- The proportion of women in psychology may have increased since I was a student

- The proportion of women may vary with sub-area of psychology

Is Oxford University biased against women?

I’m leading our department’s Athena SWAN panel, whose remit is to identify and remove barriers to women’s progress in scientific careers. In order to obtain an Athena SWAN award, you have to assemble a lot of facts and figures about the proportions of women at different career stages, and so I already had at my fingertips some relevant statistics. (You can find these here). Over the past three years, our student intake ranged from 66% -71% women: rather lower than the UCAS figure of 78%. However, acceptance rates were absolutely equivalent for men and women. The same was true for staff appointments: the likelihood of being accepted for a job did not differ by gender. So with a sigh of relief I think we can exclude this line of explanation.Does the proportion of women in psychology decline with career stage?

I have a research post and so don’t do much teaching. Have I got a distorted view of the gender ratios because my interactions are mostly with more senior staff? This looks believable from the data on our department. Postgraduate figures ranged from 65%-70% women. Ours is a small department, and so it is difficult to be confident in trends, but in 2011 there were 16/27 (59%) female postdocs, 6/11 (55%) female lecturers, 6/13 (46%) senior researchers and 4/11 (36%) female professors. This trend for the proportion of women to decline as one advances through a career is in line with what has been observed in many other disciplines. We also obtained data from other top-level psychology departments for comparison, and similar trends were seen.Has the proportion of women in psychology increased over time?

My recollection of my undergraduate days was that male psychology students were plentiful. However, I was an undergraduate in the dark ages of the early 1970s when there were only five Oxford colleges that accepted women, and a corresponding shortage of females in all subjects. So I had a dig around to try to get more data. The UCAS statistics go back only to 1996, and the proportion of women in psychology hasn’t changed: 78% in 1996, 78% in 2011. However, data from the USA show a sharp increase in the proportion of women obtaining psychology doctorates from 1960 (18%) through 1972 (27%) to 1984 (50%). This, of course, is in part a consequence of the increase of women in higher education in general. But that isn’t a total explanation: Figure 2 compares proportions of female PhDs over time in different subject areas, and one can see that psychology shows a particularly pronounced increase compared with other disciplines. |

| Fig 2. Percentages of PhDs by women in the USA: 1950-1984 |

Does the proportion of women in psychology vary with sub-area?

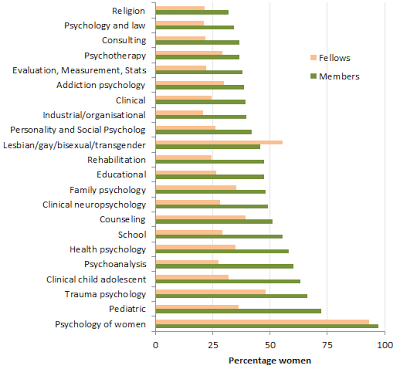

The term ‘psychology’ covers a huge range of subject matter with different historical roots. Most areas of academic psychology make some use of statistics, but they vary considerably in how far they require strong quantitative or computational skills. For instance, it would be difficult to specialise in the study of perception or neuroscience without being something of a numbers nerd: that’s generally less true for developmental, clinical, interpersonal or social psychology, which require other skills sets. I looked at data from the American Psychological Association (APA), which publishes the numbers of members and fellows in its different Divisions. The APA is predominantly a professional organisation, and non-applied areas of psychology are not strongly represented in the membership. Nevertheless, one can see clear gender differences, which generally map on to the expectation that women are more focused on the caring professions, and men are more heavily represented in theoretical and quantitative areas. Figure 3 shows relevant data for sections with at least 700 members. It is also worth noting that the graph illustrates the decrease in the proportions of women going from membership to fellowship, a trend bucked by just one Division. |

| Fig 3. Data from American psychological association: Division membership 2011 |

What, if anything, should we do?

The big question is how far we should try to manipulate gender differences when we find them. I’ve barely scratched the surface in my own discipline, psychology, yet it’s evident that the reasons for such differences are complex. Figure 2 alone makes it clear that women in Western societies have come a long way in the past half-century: far more of us go to university and do PhDs than was the case fifty years ago. Yet the proportion of women declines as we climb the career ladder. In quantifying this trend, it’s important to compare like with like: those who are in senior positions now are likely to have trained at a time when the gender ratio was different. But it's clear from many surveys that demographics changes can't explain the dearth of women in top jobs: there are numerous reasons why women are more likely than men to leave an academic career – see, for instance, this depressing analysis of reasons why women leave chemistry. In our department we are committed to taking steps to ensure that gender does not disadvantage women who want to pursue an academic career, and I am convinced that with even quite minor changes in culture we can make a difference.The point I want to stress here, though, is that I see this issue - creating a female-friendly environment for women in psychology- as separate from the issue of subject preference. I worry that the two issues tend to get conflated in discussions of gender equality. My personal view is that psychology is enriched by having a mix of men and women, and I share the concerns expressed here about difficulties that arise when the subject becomes heavily biased to one gender. However, I am pretty uncomfortable with the idea of trying to steer people’s career choices in order to even out a gender imbalance.

Where this has been tried, my impression is that it's mostly been in the direction of trying to encourage more girls into male-dominated subjects. In effect, the argument is that girl's preferences are based on wrong information, in that they are unduly influenced by stereotypes. For instance, the Institute of Physics has done a great deal of work on this topic, and they have shown that there are substantial influences of schooling on girls’ subject choices. They concluded that the weak showing of girls in physics can be attributed to lack of inspirational teaching, and a perception among girls that physics is a boys’ subject. They have produced materials to help teachers overcome these influences, and we’ll have to wait and see if this makes any appreciable difference to the proportions of girls taking up the subject (which according to UCAS figures has been pretty stable for 15 years: 19% in 1996 and 18% in 2011).

It's laudable that the Institute of Physics is attempting to improve the teaching of physics in our schools, and to ensure girls do not feel excluded. But if they are right, and gender stereotyping is a major determinant of subject choices, shouldn’t we then adopt similar policies to other subjects that show a gender bias, whether this be in favour of girls or boys?

Interestingly, Marc Smith has produced relevant data in relation to A-level psychology, which is dominated by girls, and perceived by boys as a ‘girly’ subject. So should we try to change that? As Smith notes, the female bias seems linked to a preference for schools to teach A-level psychology options that veer away from more quantitative cognitive topics. Here we find that psychology provides an interesting test case for arguments around gender, because within the subject there are consistent biases for males and females to prefer one kind of sub-area to another. This implies that to alter the gender balance you might need to change what is taught, rather than how it is taught, by giving more prominence to the biological and cognitive aspects of psychology. If true, it might be easier to alter gender ratios in psychology than in physics, but only by modifying the content of the syllabus.

One of the IOP's recommendations is: "Co-ed schools should have a target to exceed the current national average of 20% of physics A-level students being girls." But surely this presumes an agenda whereby we aim for equality of genders in all subjects, with equivalent campaigns to recruit more boys into nursing, psychology and English? I'm not saying this would necessarily be a bad thing, but I wonder at the automatic assumption that it has to be a good thing - or even an achievable thing. There are obvious disadvantages of gender imbalances in any subject area - they simply reinforce stereotypes, while at the same time creating challenges at university and in the workplace for those rare individuals who buck the trend and take a gender-atypical subject. But the kinds of targets set by the IOP make me uneasy nonetheless. The downside of an insistence on gender balance is a sense of coercion, whereby children are made to feel that their choice of subject isn't a real choice, but is only made because they have been brainwashed by gender stereotypes. Yes, let's do our best to teach boys and girls in an inspiring and gender-neutral fashion, but, as the example of psychology demonstrates, we are still likely to find that females and males tend to prefer different kinds of subject matter.

References

Smith, M (2011). Failing boys, failing psychology The Psychologist, 24 (5), 390-391 Other: WOS:000290745000037

Howard, A., & et al, . (1986). The changing face of American psychology: A report from the Committee on Employment and Human Resources. American Psychologist, 41 (12), 1311-1327 DOI: 10.1037//0003-066X.41.12.1311

*Update 10th March 2016: The link I originally had for UCAS data ceased to work. I have a new link, and think this should be the correct dataset, but I have not rechecked the figures.

https://www.ucas.com/sites/default/files/eoc_data_resource_2015-dr3_019_01.pdf

I wonder whether part of the reason could be mathematics? I imagine many people who don't like mathematics go into psychology. Then, too late, they discover that they need some. That in turn might lead to dropouts at a later stage.

ReplyDeleteJust guessing.

In Argentina most universities teach psychoanalysis which is not math and most students are women too.

DeleteStrangely enough when I was a female Widening Participation Tutor with physics A Level students the choice of physics for them was because they "weren't good at maths"! Not quite the same as not liking maths but I think they'd have readily included that too!

DeleteHi David. Not sure of your argument. Why would this lead to gender differences?

ReplyDeleteThat's the tricky bit. Is it not the case that girls are still less likely than boys to do maths at school? No doubt the difference will diminish with time, if it hasn't vanished already.

DeleteAnswer is in Table 1: 40% of maths entrants at university are women, so that would be only a small effect. Also not plausible to explain the decline in women, as a) they do as well as men in finals; b) the drop-off in numbers is most marked later on - after PhD or postdoc stage, but which time we'd hope they'd have sorted out any maths difficulties.

DeleteFrom my own experience, the most equal male:female ratio I've experienced was one male per six females (undergraduate) so I've always just taken it as read that I work in a predominantly female profession.

ReplyDeleteThis difference is perhaps most acute in clinical psychology. About 15% of clinical doctoral students are males in the UK, but 2011 was the first year that males applicants were not less likely to get a place than females.

However, I rarely see this discussed. The issue was addressed in a good 2011 article in the APA's GradPsych magazine and I wrote a short piece myself for The Psychologist but I remain bemused by the fact that there seems to be no equivalent interest in getting more males into stereotypically 'feminine' scientific professions.

Interestingly, John Radford who established A-level Psychology in the '70's said that the main aim was to encourage girls into science. Well, it worked.

ReplyDeleteFascinating!

DeleteThe title of this blog entry is "where are all the men?" but if looking at senior levels, we would need to ask "where are all the women?". This entry notes correctly that women have earned as many PhDs in Psychology as men for around 30 years, but it is still unsurprising to see good Psychology depts (especially in the Uk and Europe) with only 1 or 2 female profs, and last I checked, the ratio of Fellows of the BPS was about 4:1 men:women. This steady decline of women as one goes up the career ladder is seen in other disciplines, of course, though Psychology presents a particularly interesting case given its very heavy bias toward women at entry. I have heard a lot over the years about why this is - lifestyle choices, fear of failure, lesser aptitude when it comes to mathematics. But one hypothesis that is rarely talked about these days is good old fashioned bias. Yet, we've seen dramatic reports (the 1997 Nature study, and the recent PNAS article come to mind) that women need to perform substantially better than men to receive the same 'marks' in the evaluation of competence. Fortunately, most data suggest that the extent of bias isn't this dramatic, but in her excellent book "Why so Slow?", Virginia Valian makes the very important point that when even subtle bias is compounded at every level, it leads to a very significant disadvantage indeed. Robinson-Cox et al. (2007) have some very nice computer simulation data demonstrating this.

ReplyDeleteKathy Rastle

Thanks for your comment. I am also a fan of the Valian book and think she makes an excellent case for even subtle schema biases having important influences. I agree these can and should be tackled, along with practical issues about making the workplace more female-friendly.

DeleteBut I guess what I'm most concerned about is the rather conflicted state that you end up in as a psychologist. On the one hand, you want to do all the things to help women progress in the field and plug the leaky pipeline, but on the other hand, there's a sense that the large excess of women at junior levels is not particularly good for the subject. And in addition I am uneasy about going along with a view that assumes all gender inequalities in subject preference are undesirable and need modifying. So I feel pulled in several different directions by this topic - which is why I thought it worth blogging about!

Hi, I have been asked to prepare our Athena SWAN... this is Bristol's first application so we don't even have bronze!

ReplyDeleteWhat I find somewhat disturbing is the level of personal information that has been requested with regards to the self-assessment team.

Looking at the Oxford submission, there is in my opinion, too much personal information about marital status and family situation of the members of the team.

I can easily imagine scenarios that do not readily fit with the various norms.

This has me deeply worried.

Bruce

Thanks for raising this. We've discussed the point you raised and there will be some minor modifications made to the version on the web.

DeleteI quite agree it is vital to separate out the early years' issue - which is dominant in my subject of Physics - and the pipeline leaking, which is what happens in yours. Both are worrying, but the 'cures' are different. In everything I have said and written myself, I have always tried to make clear that 50:50 is not necessarily the 'natural' balance, but we have little else to go on. In the physical sciences, the proportion of girls entering was much higher in the old Eastern bloc, suggesting that cultural influences play a significant role.

ReplyDeleteI don't know what Cambridge's gender profile is specifically in psychology, but I do know our Vet School's which are comparably distorted: 80% undergrads are women, not a female single professor yet. Like you, I think this is potentially very unhealthy. In a previous post I wrote

"Equally, we will only get a more balanced intake by gender into Vet Schools if the Lego Vet’s office is not pink, and encourage boys to cuddle pets rather than tease them."

However, I am sure your Athena Swan application will be looking at why women aren't staying in the field (whichever sub-field they are in). What I think is so good about this scheme is that it necessitates each department analysing its own culture. As Kathy says, subtle effects can mount up, even if in themselves each are small. But positive actions can make the working environment better for everyone, men and women.

Thanks Athene: I'd love to see more information about those Eastern bloc countries: can you point me to a source? In the 1970s I had a Czech neighbour who was a chemist. Female chemists were unusual at the time and I commented on this. She explained that she had no choice in the matter: she had wanted to study arts but the state needed chemists and so that's what she did. I have no idea if this was a general trend in Communist countries, and if so, whether it persisted, but if so, this needs taking into account in interpreting those figures.

DeleteA good article on exactly this topic was published in the Boston Globe.

DeleteJust to follow up on Athene's point, preliminary indications suggest that the intake for Cambridge's new Psychological and Behavioural Sciences degree will be around 70% female. A quick count-up of the current teaching staff reveals that 38% are women including, perhaps unusually, 43% of our active Professors. I'd certainly agree with both Dorothy and Athene that having a good mix of male and female colleagues makes the department a much better place to work for everyone.

DeleteJust an anecdote (note typical female deprecation), but when I took Oxford's PPP course (physiology, psychology, philosophy), plenty of people chose to do Psych+Phil to avoid the hard science, while those more interested in bodies than minds went for Phys+Psych.

ReplyDeleteThinking further, does anyone know of any data looking at the personal/nonpersonal preferences as a potential contributor? I don't mean to the extent of e.g. Baron-Cohen's systematising-empathising dichotomy, just the idea that some people like working with people and others don't.

ReplyDeleteI'm puzzled by "The UCAS statistics go back only to 1996, and the proportion of women in psychology hasn’t changed: 78% in 1996, 78% in 2011."

ReplyDeleteWhen I looked at this in 2009 I found there had been an increase (that had flattened out over time):

http://seriousstats.wordpress.com/?attachment_id=329

I used HESA data (registrations or completions?) rather than UCAS data (applications or admissions?).

If psychology was seen as focussed on causal explanations of the brain and mind, we'd have plenty of bright entrants. Instead it's often fact and theory lite (easy/undemanding in terms of system II activity), and an entry to caring professions.Jointly I think these explain both the gender bias and the difficulty in getting ambitious smart students; they often come in sideways from other subjects having avoided most of our undergrad. Perhaps time for a different year one: something full of causal reasoning, data heavy from day one, and holding out the prospect of really exciting breakthroughs?

ReplyDeleteTim,

DeleteI write a post saying we have a surplus of women entrants into psychology,and you respond by saying there's a difficulty getting ambitious smart students.

You seem to be equating 'ambitious smart students' and 'bright entrants' with men.

That's both offensive and wrong - we have no shortage of bright female applicants.

At the risk of being a data bore, as I still have my spreadsheet open: As mentioned in my earlier comment, female applicants make up around 70% of Cambridge's likely intake for Psychology next year. However, of the top 20 applicants, whose A-level performance is about as stellar as is possible to achieve, 90% are female. Thus, Tim's comment is not just offensive but not borne out by data.

DeleteDear Dorothy,

DeleteMy suggestion was not that women are less talented. Instead it was that if we aren't recruiting from half the population it will halve the number of exceptional people available to the field.

@Jon Simons I neither said nor implied that female applicants are less able than male applicants, quite to the contrary in fact: the sex differential means that almost all the stellar applicants must be female, as you confirm.

The question is how to let these "missing males" know that psychology is an exciting area, and make our courses attractive to retain this different audience. Perhaps generate undergraduate content more like the post-graduate content which seems to retain men more effectively?

I studied psychology as a mature student in 1989. Mature students were admitted if they could provide evidence of a good work ethic and attain a certain score on Raven’s Progressive Matrices. This method was as good a predictor of final degree grade as A Level scores. Half of the men on the course (still only 25%) were older, and from a skilled manual, or manual, work background. When the admission process was changed to include an interview it was a poorer predictor of final grade with “middle class” women out performing their final degree mark in interview. The admissions tutor was a meticulous statistician and I take the gender observation to be accurate and the class observation to be an anecdotal.

ReplyDeleteI suspect that with the increased importance of modular A Levels, and personal statements, and the academic publish or die culture there has been a shift in favour high verbal intelligence over general intelligence. This seems always to have been a disproportionately large weakness for men from the lower socioeconomic groups and it is this group that may have been squeezed out. Even statistics seems to have been turned from an exercise in numeracy to one of literacy. I have returned to study and have had to replace my slim but adequate penguin text with Andy Field’s 800 page tome. I don’t think that I have read an 800 page book since I was 15.

Very often I read blogs or articles in which describe how unsympathetic men can make life difficult for women and what needs to be done to make work female-friendly and not “uncomfortable for women”. Having largely worked in all male organisations (military, manufacturing and construction) the behaviours described are not to me, typically male, but seem to be normal working class speech and social habits. They make me just as uncomfortable but I have had to learn to deal with those people as they are. Two points arise from this. Firstly, understanding what makes women “uncomfortable” should not be allowed to become a shibboleth by which only middle class students are admitted. Secondly, growing a thick skin is entirely necessary for effective leadership. Empathy and understanding will only get you so far. Objectification and instruction are just as important. Someone who needs their workplace to be always comfortable and friendly is probably not cut out for leadership. At least that is what they teach you at Sandhurst, and they should know.

Regarding the sex differences between degrees and faculty, while sociological issues and bias are definitely major factors, there's one additional thing that I didn't see mentioned in the post or existing comments. A non-trivial number of faculty in psychology departments didn't get their degrees in psychology. They might have been trained as neuroscientists, engineers, physicists, computer scientists, etc, but to research that fits well in a psych department. These fields have a slight to huge male bias in degrees earned. This doesn't explain the full male-skew in psych faculty, but I could guess it increases the skew by a few percent.

ReplyDeletei live in Bangladesh where most of psychology professor are women. and if you collect data from our country you will find counselors are women most of time i have seen. i do not know why?

ReplyDelete